The “Me too” movement from Hollywood to your bench

by Mayank Chugh, Alba González & Julian David Rolfes

Sexual harassment is an endemic and dismissive predation that is as prevalent in academia as it is in other fields and workplaces. Certainly, in all cases, dominance and power have made harassment and its concealing properly executable. Women worldwide can surely attest to it.

While the stories about assaults are outspoken and highly relatable, the voices against the perpetrators are quiet. Recently, the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements that gained momentum in response to the Harvey Weinstein scandal have encouraged women globally to come together, share their stories and create awareness of sexual harassment - a menace that penetrates cultures and nations. Although these movements and stories are from Hollywood, their roots and messages are not. They are now a testament of sexual misconduct in the workplace. There are many such stories that lie hidden at domestic workplaces and benches across the world.

This article is in support of #MeToo, #TimesUp and the other unheard voices to raise awareness of sexual harassment, especially in our offices, labs, and in academia.

#MeToo – Talking about sexual harassment

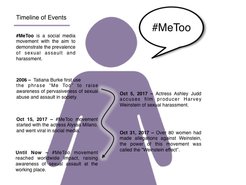

The #MeToo movement dates back to 2006 when American civil rights activist Tarana Burke used the phrase “#MeToo”, the only thought she could think of, in response to a woman who confessed to being a victim of sexual violence. This phrase was meant to raise awareness of the pervasiveness of sexual abuse and assault in society, and became increasingly famous over time.

Eight years later, as a result of previously reported sexual harassment cases inside the film industry, the well-known activist and actress Alyssa Milano unleashed the #MeToo movement on Twitter, encouraging sexual harassment victims to post “MeToo” as part of their status update. #MeToo gave a voice to other well-known actors and actresses, and tens of hundreds of others who have been sexually harassed by their male peers. This triggered a chain of consequences for the offenders, where many were put in quarantine, got fired from their jobs or were formally impeached.

The reach and impact of the #MeToo movement went way beyond the red carpet. It has become an international movement, raising awareness of sexual violence around the globe. Moreover, it highlights the prevalence of sexual violence in certain workplaces, such as the financial, political, military, and academic environments. Women are especially vulnerable in these environments where they face underrepresentation, fierce competition, and where men thrive in the scale of power.

The Weinstein effect and #MeToo have also inspired the birth of the #TimesUp movement from Hollywood celebrities, thus creating more awareness and giving a voice to the women in the entertainment industry and at their workplace.

The #MeTooPhD – Sexual harassment in academia

Academia, as we know it, is a highly hierarchical field. The people in power are the gatekeepers of careers and funding opportunities, and sadly, most of them are men. Academia is just like Hollywood for a variety of reasons. First, men in academia outnumber and shadow women to a very significant level. In the last few years, efforts have been made to promote gender equity in academia with women making it to universities and positions of power; however, it still requires strenuous determination and time to reach even close to equality. Second, the field of academia is hyper-competitive as there are only a few professional opportunities available compared to the long list of qualified and talented aspirants.

Given the cultural diversity and international environments in our offices and research labs, one might imagine that we are way above traditional gender stereotypes and are in an equal and scientific endeavour. We might imagine professors and students going to dinners, conferences, retreats, and getting drinks together. However, this is not the case. Women in academia are still sexually assaulted and harassed by men in power, and due to the tight job market, their voices remain quiet. The ones who choose to speak up are forced to switch jobs entirely, depriving the field of their talent, their passion, and their insights.

In the wake of the #MeToo movement and to show how ubiquitous the problem of sexual harassment is in academia, former tenured professor Dr. Karen Kelsky at the University of Oregon and Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who now runs an academic job consultancy blog, ‘The Professor is in', launched an anonymous survey and #MeTooPhD tag on Twitter in December 2017. The aim of this survey is “Providing a place for women to share stories without fear of censorship or judgement, to know they are not alone, and to find strength in numbers and a foundation from which to recover and perhaps take action”, writes Kelsky on her blog. This anonymous survey contrasts law student Raya Sarkar’s initiative, which released a list with professors’ names who were accused of sexual harassment, promoting the “naming and shaming” tool against sexual abuse.

Kelsky’s survey spreadsheet has more than 2000 entries as of April 27th, from over 30 fields of study. The survey shows that most entries are from graduate students, followed by undergraduate students, non-tenured and tenured professors. The stories on this survey share the well-known symptoms of sexual harassment, as Kelsky points out. First, the ubiquity and severity of sexual abuse ranges from glances to proper stalking for months and years to intimidation and rape. Second, there is ‘the sheer force of patriarchal solidarity’ that protects the assaulters over victims. This, once again, speaks to the power and dominance that rests in patriarchal academia. Third, there is the loss of women from academia. Many women who shared their stories confessed to a change or loss of projects, supervisors, institutions, and/or funding.

These problems are unsurprising to the women in academia. Many women can relate to it and speak about how pernicious the problem of sexual harassment in academia is. In one of the Quartz interviews, Dr. Rebecca Kukla, a Philosophy Professor at Georgetown University, says women have become used to such male behaviour – ‘guarding their bodies and keeping things professionally whenever any acts happen. It’s a part of job training’.

The truth is many women worldwide struggle with anxiety, vulnerability and confusion about the daily misconduct at their workplace, in addition to keeping their families and careers together. The question before us now is: what can we do as a community to safeguard women, to give voices to long-silenced victims and to encourage them to speak up against their assaulters?

From #MeToo to #Oprah

The Max Planck Society (MPS) released an official statement about sexual harassment and sexual violence. Besides a summary of the legal situation in Germany, including the definition of the terms ‘sexual assault’ and ‘sexual violence’, the statement also includes a recommendation for disciplinary actions for employers, “ranging from admonition and warning to transfer to a different workstation ... up to dismissal”. The employer is also encouraged to take training as part of the disciplinary actions, as well as preventive and clarifying actions. However, the fact that no MPS-wide guidelines exist to this effect makes the appropriateness of the disciplinary action completely dependent on the employer.

Lastly, the possibilities for victims are summarized, i.e. talking to the internal EO Officer, the MPS Central EO Officer or the Works Council. It’s noted that complaints can be made “informally, including verbally or electronically.“ While the person concerned does not have to be informed until consequences are agreed on, the contact between the victim and the offender should directly be minimized as far as possible.

However, we still stand at the same spot. Max Planck Institutes are also quite hierarchical, once again making reporting difficult. This is especially true considering offenders are often the ones who would decide on disciplinary actions. The fact that there is a lack of strict guidelines from the MPS is another impediment to the reporting of such cases.

Although the MPS is aware of the impact and prevalence of sexual violence and has formally created a guideline, more effort should be put towards enforcing specific actions against the offenders irrespective of power and to create an appropriate platform for reporting cases of sexual assault. The Equal Opportunity group at the Max Planck PhDnet fights for these rights.

While the institutional and legal actions take their own shapes and ways, we as colleagues, as men, as women and others who we choose to be, should stand in solidarity and support the voices of those who suffer. As Oprah Winfrey put it in her recent Cecil B DeMille win, “When that new day finally dawns, it will be because of a lot of magnificent women, and some pretty phenomenal men fighting hard to make sure that they become the leaders who take us to the time when nobody ever has to say, ‘Me too’ again.”

To read the Max Planck Society's statement on sexual harassment and sexual violence, please visit https://www.mps.mpg.de/5054710/Sexual-harassment-and-sexual-violence.pdf

Contact of the Central EO Officer: Dr. Ulla Weber (ulla.weber@gv.mpg.de)